Karachi’s streets are both its circulatory system and its skin.

The city, with a population of 20 million, has a total of over seven million registered vehicles. Buses, trucks, cars, and motorcycles crisscross more than 9,500 kilometers of the roadway, and with the passage of time heavy traffic has taken its toll. But Karachi’s roads are also uniquely vulnerable to elements such as water, especially during the heavy monsoon season it witnesses between the months of April and August.

If you cut open the surface, there is yet another complication to the well-being of its bloodstream — a complex web of infrastructure that either dates back ages and narrates a tale of half-hearted efforts at construction or upkeep.

No single authority entirely controls what goes on in the city’s subterranean tunnels and tubes. Instead, a bunch of bodies cut through the asphalt whenever they want to, either for maintenance of basic amenities such as electricity and gas or for a promising new project that never delivers.

Unfortunately, the coordination of these projects and repairs, along with the provision of decent roads, is always a colossal endeavour, and one such example is at display in the city’s ‘elite centre’.

An open heart surgery

Like several others in her locality, Hafsa* — a middle-aged woman living in the Defence Housing Authority (DHA) Karachi — has been facing the brunt of an open heart surgery under way just outside her residence in Lane 11 of Khayaban-e-Badr in Phase IV.

“They have cut open the street right in front of my house. If you’re not careful while stepping out, you might just fall to your death,” the mother of two told Dawn.com.

At the mouth of the lane, a small board saying ‘CAUTION’ hangs on one of the electricity poles, barely visible to anyone driving by.

Some five steps from the main entrance to Hafsa’s house, the road has been dug down to almost six feet. Old pipes — that residents say carry both rain water and sewage — can be seen underneath the asphalt, with filthy water leaking. Nearby, cement blocks have been piled up vertically, almost waiting to get laid. As you move forward, the leaking water fills up to the neck of the grubbed-out parts of the lane.

“The way this construction is under way, it is nothing less than lethal for us,” Hafsa told Dawn.com. “My child has been sick for the past few days because of these mosquitoes and even taking him to the hospital is a major feat.”

She said the construction outside her residence began nearly four weeks ago and was slated to be complete by Eid, but the progress had been very slow. “Our cars have been parked inside the houses for days now because it is impossible to take them out.”

She complained that no one from the administration had informed the residents about the construction beforehand, giving them almost no time to prepare. “They just showed up one day and started digging. Our entire street smells so bad. We can’t go anywhere, neither can anyone visit us. Is this some kind of torture?

“See, we don’t have any issue if there is a development project under way. But they ought to give us details right? Isn’t this a basic right?” she questioned rhetorically.

Hafsa is among several DHA residents, some of whom have waited for months now for the trenches outside their houses to be finally packed and repaired with cement. But their wait keeps getting prolonged with each passing day.

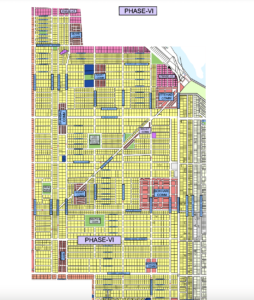

Aasiya*, a designer who runs a boutique on 3rd Commercial Street of Phase VI, told Dawn.com that she was among the few people in her area who was informed about the construction — under way for a stormwater drainage project — beforehand.

“When they told us that they were doing all this to stop DHA from getting flooded, we were more than happy,” she said. “But looking at the work they have done until now, it seems as if it will take them a year to finish it.”

The designer also expressed fear that if the project was not completed before this year’s monsoon rains, the havoc that would be caused “will be unprecedented”.

Asiya’s son, who studies at a college nearby, also said that the project seemed to be unplanned. “When you are working on such a huge area, you need to identify and create alternative routes for residents. But there is no planning here. I have to leave an hour early for college because the main intersection near my house is jam-packed every single day.”

The infamous project

Amid the chaos endured by the residents, the DHA spokesperson, calmly but very briefly, explained to Dawn.com the reasons behind the critical surgery under way in many areas falling under its jurisdiction.

In the last three years, he said, DHA had been severely affected by urban flooding due to the lack of a stormwater drainage system.

“To cater to the urban flooding, loss to properties of the residents and psychological disturbance, [the construction of] stormwater drains [spreading to approximately 76kms] were planned to cater to more than twice the intensity of the 2020 rains.”

The 2020 rains had wrecked havoc in the posh locality and brought life to a standstill. Homes were inundated and the streets looked like a part of the Arabian Sea, with nothing except water in sight for kilometres. Throughout the ordeal, residents had only the DHA and Cantonment Board Clifton (CBC) to blame.

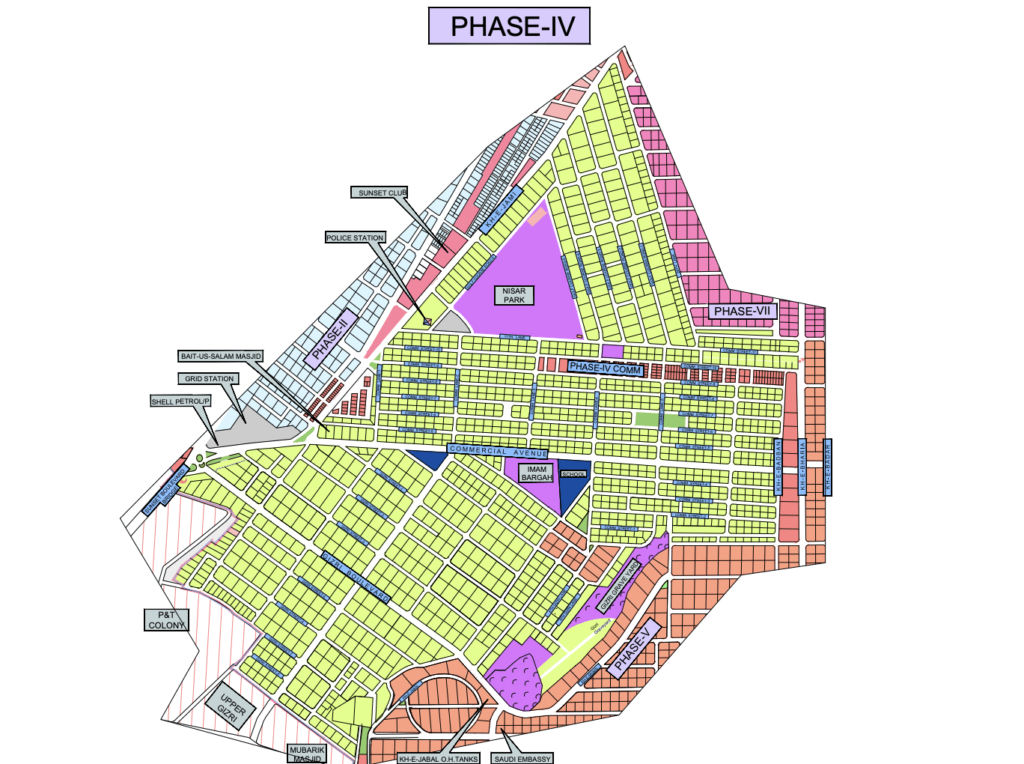

Therefore, during the new project — which commenced in September 2022 and includes all the phases, khayabans, and avenues — Phases IV and VI had been highlighted as critical areas because of the extent of damage caused here previously.

With regards to the project timeline, the DHA spokesperson said that its construction was met with several challenges, “including high subsurface water tables, loose and strata, shifting of utilities and services” and old sewage infrastructure.

He told Dawn.com that the entire project was scheduled to be completed by March 31, 2024. “However, critical areas of Phase IV and VI [covering more than 40km] is being currently undertaken and will be substantially completed prior to the onset of the monsoon “to provide maximum relief to the residents”.

“All stakeholders are on board from the outset and have been pursued vigorously for early shifting of utilities/services for the construction of the drains/roads,” he explained, promising that there would be significant improvement by the end of May 2023.

The spokesperson added that asphalt on more than 4km had already been laid, pointing out areas such as Khayaban-e-Ameer Khusro, Khayaban-e-Muhafiz, Commercial Avenue, and others.

He also explained that the outfalls of three stormwater drains on the right of the Khayaban-e-Hafiz will discharge in the Mahmoodabad Nullah, while five others — in the left direction — will discharge into the sea.

Dawn.com had asked the DHA for a map of all the areas where construction was under way or had been completed, but they refused to share it.

A story that needs to be told

Before we delve deeper into the new stormwater drain project, there is a story that needs to be told and it goes back to the 1950s.

In 1953, the Pakistan Defence Officers Housing Authority (PDOHA) was formed and registered under the Cooperative Societies Act, 1925. The authority described itself as a welfare society in which members, to whom the land was allotted, were people who have once served in the army.

However, the PDOHA did not stay a society for long.

In 1980, military dictator Gen Ziaul Haq passed a presidential order, converting the society into the Defence Housing Authority (DHA). The latter was given extraordinary powers, allowing it to make its own rules, masterplan, and exercise total control over all the municipal functions. Despite all these powers, however, the authority has largely failed to do its job, as the sorry state of the current stormwater drainage system suggests.

The problem was first witnessed in 2007 when the monsoon rains in Karachi broke a 90-year record with a 17.22mm downpour recorded in just an hour. The entire city was submerged and scores of people were killed. But the destruction in DHA was the worst as residents of the posh society were left aghast, looking on to their desolate neighbourhood, once sprouting with freshly designed houses.

What was hailed as a modern developed society looked like an elite katchi abadi.

As the anger of the residents erupted like lava — in the form of protests and demonstrations — authorities rushed to find solutions and after a thorough inspection, it was concluded that the DHA did not have stormwater drains in the first place because developers had never predicted massive rains in Karachi, given its dry season in the 1990s.

The situation was now deemed critical and so they hired a man, Bashir Lakhani, to do the job for them. A Rs2.3 billion plan was drafted, which was supposed to be implemented in three phases — but was abandoned before completion. (This is where DHA got its gad-gad-gad roads from)

In the first phase of the plan — which was successfully completed — stormwater drainage lines were laid in the middle of the road and were covered with concrete slabs that featured slits to allow the water to drain through. If you drive through DHA often, you would be well aware of these roads. This was a plan that no engineer would have agreed to in normal circumstances because the developers had left no space on the side of the roads for a water channel. But Lakhani agreed to do it as it was the only viable option at the time.

Now the first phase of the plan was completed, but the subsequent two phases — which included shifting the inlets from the middle of the roads to the sides and finally carpeting the road — were left hanging because the project was scrapped. Why? There was a lack of funds.

DHA wanted residents to pay for the drainage system, a price in millions of rupees, but the latter refused to do so.

“They wanted the residents to pay the cost of the stormwater drainage lines in the form of a refurbishment tax which was in millions,” Nasir Jehangir, president of the Defence Society Resident Association (DSRA), told Dawn.com.

He explained that it was clearly stated in the lease papers, a contract between DHA and the allottee, that the authority would construct a stormwater drainage system — the charge of which residents had already paid in the form of a development fee when they were buying land in the society.

A development charge is paid by the allottee to the authority. The charge is meant to cover expenses incurred when the authority makes roads, sewerage drains, stormwater drains, public spaces, parks, and all public amenities.

What followed were several discussions between the residents and the authority but all of them failed, after which the matter ultimately went to court. The fiasco resulted in a stay order on the project.

In spite of that, even the half-complete project had given DHA what it didn’t have at all — a shabbily put together storm water drainage system. But then came the 2020 rains, another disaster and a harsh reminder of the 2007 showers. The destruction was the same, if not more, and so was the anger among the people.

Ahmed Shabbar, a DHA resident and the Founder of Pakistan Maholiati Tahaffuz Movement, was among those who repeatedly wrote to the authority, demanding answers. When they did not get a satisfactory response, some 80-100 people filed a petition in the Sindh High Court.

In the subsequent days, the court ordered DHA to hold a meeting with the residents to resolve the drainage issue. But, according to Shabbar, not a single meeting has been held between the two parties to date.

You would ask why this story is important. Because Jehangir told Dawn.com that the new drainage project, which was launched last year, is exactly the same as the one that was supposed to be the Phase 2 component of Bashir Lakhani’s project.

“But instead of completing what was left midway, they have just dug everything up without any sense of planning or directions,” he said.

‘A 100pc failure’

According to Jehangir, the new project is a “100pc failure”.

He said that even though DHA claims to have a complete design for the project, the company the authority had handed over the work to — Zeeruk International — did not have the required specialisation, experience, or expertise in the construction of stormwater drainage systems.

“We have heard they have paid more than a billion rupees for the design. But they are just digging up the roads next to the pre-existing drain to put in new drainage lines parallel to it.”

Despite several attempts to contact them, Zeeruk International did not respond to Dawn.com’s requests for details of the project.

Jehangir added that in some areas, the drainage lines that have been dug up have stagnant water standing till its mouth, with no way for it to be moved out. In several places, warning signs are missing too.

An engineer, who asked not to be named, highlighted that there were major problems with the new project. Firstly, he said that was a major lack of planning.

“Ideally, the work should have been completed by April this year, especially with the rains already coming down. But we have gotten complaints from a lot of areas that the digging has just begun there. This is very dangerous and can cost people their lives,” he told Dawn.com.

Meteorologists and weather experts had predicted at the start of the year that Pakistan would witness erratic monsoon rains in 2023. Similar forecasts have also been issued by the Pakistan Meteorological Department. But it looks like they were not taken into consideration.

The engineer went on to explain that every project required a timeline, which he stressed needed to be followed immaculately. “Now if it starts raining, with all these roads dug so steeply, anyone can fall into them. The situation is so bad that you won’t know if the next step you take will land on the road or down to your death.”

The second issue highlighted by the engineer was that of pumping. He said that this year, DHA was depending a lot on pumping. “Let me tell you, the pumps won’t even meet 1/5th of the requirement,” he warned. “It is simple logic. It doesn’t rain in Karachi throughout the year, so after the two months of monsoon, these pumps won’t be used and hence won’t be maintained. They are nothing but a waste of money.”

Moving on to the next flaw in the system, he pointed out that before laying down new drainage lines, DHA should have first separated the sewage lines from the stormwater drains. “Unfortunately stormwater drains have been converted into sewage lines across Karachi, but this should not be the case.

“Both these lines should be different because otherwise, stormwater will never be able to be drained out. The sewage will always block the flow,” the engineer added.

The same was also pointed out by experts at the NED University of Engineering and Technology, who had been instructed by the court to evaluate the new stormwater drainage project. In their report, the varsity had clearly stated that the present design “may be inadequate if the stormwater drainage system was also catering to the sewage flow”.

Architect Arif Bilgaumi, meanwhile, expressed his own set of concerns regarding the planned drainage system.

“Typically, stormwater drainage should pass through a settlement chamber where silt and debris can be collected. Otherwise, the drain will get choked. There is no such provision in the design,” he told Dawn.com.

Bilgaumi explained that all sewage lines had these chambers so that solid waste settled down instead of choking the lines. “When sanitation workers are seen climbing into manholes and cleaning them out, this is what they are cleaning,” he added.

However, the architect pointed out that the new stormwater designs, shared by the DHA with residents, showed access grates in the system but there was no space to get in and clean the drains as they extended for kilometres on end. “If you instead had a manhole with a catch basin, the solid waste would have just settled there and wouldn’t have gotten into the drain.”

In the new design, the inlets did not have sumps, a pit or hollow, in which liquid collects, and therefore the drains could only hold water at half their capacity because the remaining space would be consumed by the waste, Bilgaumi added.

Unkept promises

While all these shortcomings continue to persist, for the residents of DHA, what matters the most is their well-being and most of them are ready to trust the authorities with it. Unfortunately, their hopes have often gone down the drain in the past, unlike the water during the rains.

DSRA President Nasir Jehangir told Dawn.com that when the digging first began, the residents had been promised services such as free guarded parking, shuttle services, and fumigation by the DHA.

“All these were just lies. People are stuck in their homes, they can’t take out their cars. They can’t call in ambulances to their streets. They have to hire guards and pay for car parking from their pockets,” he said, adding that in several areas, cars had slipped into the trenches.

In other areas, the digging goes down so deep that walls of surrounding houses have started cracking, said Jehangir.

“DHA is a mess and now they have started closing things abruptly. We don’t know what they are hiding,” he said, adding that none of the residents had shown confidence in the new system and highlighted that the reasons behind it was that no one was shown the design nor was their input taken.

“We are the ones living here, who can tell you better than us the problems we face.

“The administrators don’t listen to us, each administrator blames the last one. They may continue doing it. But the reality is that the authority as a whole is responsible.”

This story was originally published in Dawn.com