Blinding Lights: How Artificial Lights Affect Marine Ecology

No acknowledgement, let alone regulations, in sight regarding artificial light pollution across Karachi coast

Blinding Lights: How Artificial Lights Affect Marine Ecology?

No acknowledgement, let alone regulations, in sight regarding artificial light pollution across Karachi coast

As the sun set over Karachi, we left behind the bright lights of the city and headed west. Our goal was to visit Mubarak Village, where the night sky was not polluted by artificial light but illuminated by countless stars. We were a team of three reporters from The Citizenry curious to explore the contrast between the natural light and artificial light at night (ALAN).

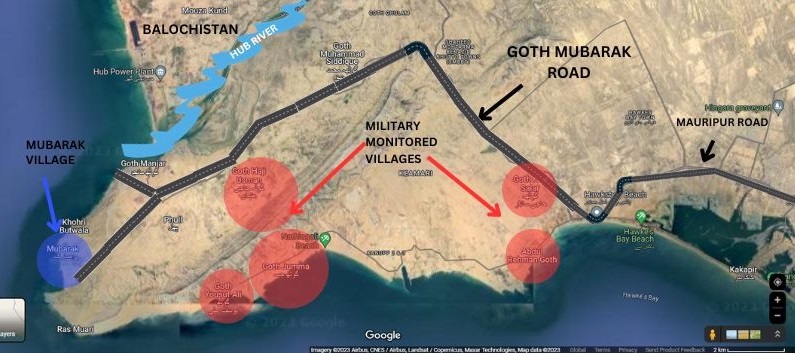

We were guided in our mission by Muhammad Zahir, a fisherman and part-time picnic van driver. Around 10:30pm on Sunday, October 15, the four of us were seated in a black Japanese 660cc car as we carefully traversed the bumpy and unlit Goth Mubarak Road with our car’s headlights leading the way. Zahir, a resident of the village, gave us directions to a shrine, the darkest spot in the area. On one side of the road were bare hills, covered in spots with pale green thorny shrubs, shadowing military-monitored rural settlements. On the other, was a shoot-on-sight coastal zone with military personnel.

We crossed through an army check post and reached the village. The houses comprising cemented painted structures and huts looked uninhabited. Not a soul was in sight. We were astounded by the silence in this hamlet of 565 houses with 2,390 people (2017 census) when we got there at 11pm. The only sounds were the barking of stray dogs and waves slamming against the shore. The village was without power and mobile signals barring a few houses equipped with 12-watt white LED lights, a.k.a energy savers, lit through solar panels. Zahir lived in the village along with his wife, three children and parents in a 200-square-yard compound comprising three bamboo huts.

12-watt white light installed at Zahir’s house. Picture taken on October 17 at 4:47 am. Picture by Oonib Azam

Night view of Zahir’s 200-square yard compoud comprising two bamboo huts. Picture taken on October 17 at 4:49 am. Picture by Oonib Azam

Inhabitants here follow the rhythm of the sun and the moon. Everyone heads home when the sun sets. By 9pm, the entire village is sound asleep except for a few youngsters who might sit by the sea for some fresh air, said Zahir, a lean man who chatted with us in Urdu. As he spoke, I looked at the star formations sprinkled over Mubarak Village sky which were luminous compared to the horizon of Karachi’s densely populated areas.

The coast of Mubarak Village is abundant in intertidal rocks and coral patches. These are home to red crabs which are a source of income for village fishermen. The red crabs are not found in other sandy beaches of Karachi. “These crabs reside inside the rocks and feed on small snails,” he told us, unused to the darkness all around save for the natural light coming from the moon and stars.

At around 12:30 am we gazed at the sea watching its crests and troughs. Clouds drifted across the night sky. The air was refreshing because of an earlier spell of rain. “Look at the blue waves!” shouted an excited team member pointing towards the glowing ripples. “It’s so common here,” Zahir said casually. For him, it was. But for us city dwellers this was an unexpected and unique spectacle. As we watched the waves recede, sand grains glistened resembling miniature gemstones. I scooped out some, holding within my hand, grains of the sapphire sand. Zahir told us that these lapis lazuli lights guided the lost fishermen back to the shore.

Bioluminescence is the name of the blue glow that lights up the sea. It is a coded message that marine creatures use to communicate in the ocean. The creatures create their own illuminations through chemical reactions inside their bodies. Bioluminescence was not only found in the depths and dim parts of the ocean, but everywhere, said Dr Sadia Khalil of Karachi’s Pakistan Marine and Environment Lab. From bacteria and plankton to arthropods and fish, many aquatic creatures produced this light either to scare their predators or to lure their prey.

So, as we switch to newer, energy-saving lights, we might be unintentionally disrupting the “underwater light language that these creatures have been using for ages,” she said.

According to Moazzam Khan, the technical advisor on marine fisheries at WWF Pakistan, coral patches around Mubarak Village and surrounding areas like Cape Mount and Churna Island were not directly impacted by ALAN, but by high sea temperatures.

Karachi’s coastline faces light pollution

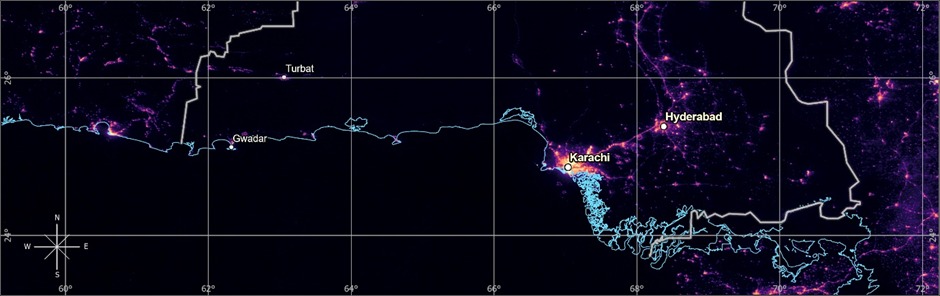

According to the National Institute of Oceanography‘s (NIO) Integrated Physical Oceanography Lab (IPOL), light generated in Karachi at night covers a distance of 2,821.7 square kilometers offshore. Or, put another way, when seen from space, Karachi would be visible as a lights cluster with its Keamari port facing the Arabian Sea as the most lit.

The coast of Karachi, the largest city in Pakistan, stands out as a cluster of bright lights when viewed from space. Picture credt: NIO’s Integrated Physical Oceanography Lab

Increasingly, the international scientific community is carrying out studies to show light as a pollution source that has the potential to harm natural environments. Dr Thomas Davies, a marine conservation lecturer based at Plymouth University, UK, pointed out in his 2014 research paper that almost 22 percent of the world’s coastlines were currently exposed to ALAN, with Asia having the second highest percentage of coastline influenced by light pollution after Europe. Thus, it can be deduced that Karachi’s coastline was exposed to artificial light.

To go a little deeper, The Citizenry used the 2017 population census from the Pakistan Bureau of Statistics website, and calculated that about 31.6 percent of Karachi’s total area or 3,527 sq kms was situated near its coastline with 14.7 percent of its total population or 16.051 million residing in the area.

Mubarak Village was one such coastal area surrounded by seawater on three fronts. The Hub River on the western side of the village separates it from the Balochistan province. As the village was located in the remotest part of Karachi and far from the port, it was least affected by ALAN.

Screengrab of Goth Mubarak Road and adjoining military monitored villages, among other spots. Curated by The Citizenry

Scientists and researchers measure ALAN by using satellites. To measure the light radiance they use a unit called Watts per steradian per square centimeter (W sr-1 cm-2 or W for this report). In other words, they measure to what extent light intensity exists in each square centimeter of an area. Thus, when Mubarak Village’s ALAN was measured, it was between 0.8 and 1.3 W, a negligible figure in terms of light radiance.

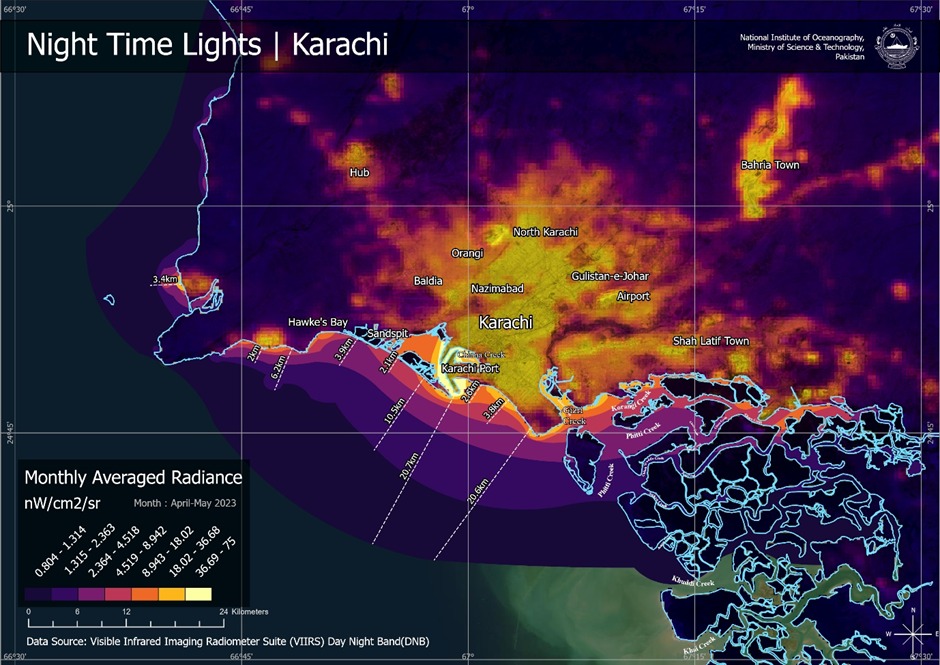

The Karachi-based National Institute of Oceanography’s (NIO) IPOL used remote sensing technology to estimate the extent of artificial light onshore and offshore on the Karachi coast for the months of April and May. Onshore means the shoreline and some land attached to it while offshore means away from the shoreline and no land attached.

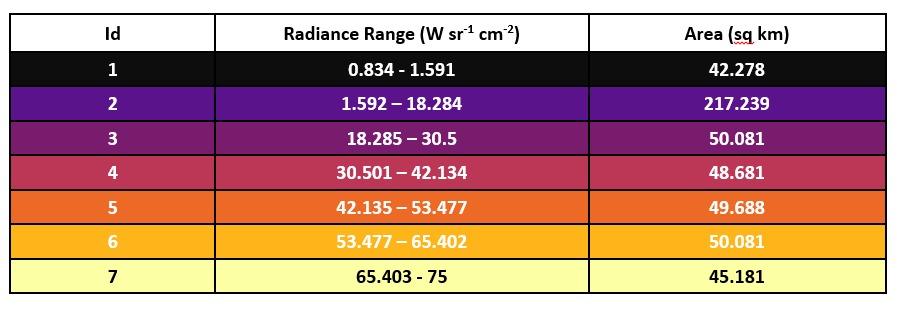

The NIO created buffers or zones (see map and table below) to illustrate different levels of offshore light radiance. These buffers represented by different colours on the map and table below indicate varying intensities of light. For instance, bright yellow indicates the highest light intensity while purple the lowest. As light travels further from its source, it loses intensity, which is also depicted by these buffers. This method is often used in oceanography to visualise data spatially.

The table displays offshore light intensity in square kilometers areas. Table by NIO’s Integrated Physical Oceanography Lab

Their analysis showed that the highest ALAN intensity was spread over an area of about 10.04 sq kms around the Karachi Port Trust (KPT), an area so immense that it equals 1,287 football stadiums. As for its light radiance, it ranged between 36.69 and 75 W equalling light emitted by 22 stadiums. Also, the artificial light emitting from KPT went as far as 20.7 kms into the sea with an ALAN radiance ranging between 0.804 to 1.312 W that extends beyond 10.5 kms offshore.

Offshore light radiance in various buffers across different color bands. Illustration by NIO’s Integrated Physical Oceanography Lab.

The difference in ALAN radiance figures was because light is intense near the shore where seawater is shallow and weakens as the sea gets deeper, explained Waqas Ahmed, a remote sensing and geospatial information researcher at the Hasselt University, Belgium who was in Karachi when I contacted him to make sense of NIO analyses.

The second highest ALAN intensity calculated by NIO was near Emaar Pakistan, and along the Gizri Creek and the Seaview Beach ranging between 18.02 and 36.68 W or in other words it was as if light was emanating from 11 football stadiums.

The highlighted spots mark the most artificially lit residential-cum-commercial areas, second only to KPT. Curated by The Citizenry

This is not surprising as I and our Citizenry team had a first-hand view of the vicinity a few hours earlier before our Mubarak Village visit. At around 8pm, our car headed towards the Seaview Beach where we saw amblers recording videos. We looked at seabird flocks foraging for their food between the ripples of the surface. We heard sea waves crashing against the shore.

Screengrab to register the context and contrast of the two coastal spots discussed in the story. Picture by The Citizenry

We went towards the Captain Farhan Ali Shaheed Park, 27 meters from the sea, where a festival was in full swing. The enclosure was fully illuminated, the atmosphere lively. We saw beacons of light glimmering the sky at a distance way beyond the park.

Emaar Pakistan, a gated housing society, located roughly 3.7 kms from the Shaheed Park is known for its luxurious amenities such as a futsal court, members-only clubs and seafood restaurants. These facilities are excessively lit, especially on weekends. The society was built on illegally reclaimed land from the Arabian Sea and lacks the mandatory Environment Impact Assessment (EIA) approval from the Sindh Environmental Protection Agency (Sepa). Covering an area of 30 hectares (equivalent to 38 football fields), the project emits light along the shoreline with an intensity ranging between 30.501 and 42.134 W. The latter figure is comparable to light emitted by about 12.5 football fields.

Alongside the shore of the Gizri Creek area, home to unauthorized restaurants, hotels, wedding halls and a golf club there were two levels of light intensity: the first ranges between 53.477 and 65.402 W. The second ranged between 42.135 and 53.477 W.

The NIO studied ALAN’s impact onshore. They assessed 503.2 sq kms of onshore area of which only 42 sq kms or eight percent experienced minimal to none impact by ALAN. These places include Mubarak Village and its vicinity.

The NIO created buffers with colours, also, for onshore light radiance. Bright yellow is the highest light intensity and black lowest. Thus, KPT’s shore is bright yellow because it has between 65.403 W and 75 W of light. See map and table below.

The table displays onshore light intensity in square kilometers areas. Table by NIO’s Integrated Physical Oceanography Lab

Onshore light radiance in various buffers across different color bands. Picture credit: NIO’s Integrated Physical Oceanography Lab.

We compared KPT’s light intensity with Jakarta’s Tanjung Priok port. Tanjung Priok is the world’s 22nd busiest port and KPT is the 83rd. According to a 2020 World Bank blogpost, the Jakarta port had 130 W light intensity. KPT was 75 W bright in April and May last year.

Usman Ghani, a quality and environment auditor, went through the blogpost. He explained to The Citizenry both ports used similar methods to calculate ALAN but Tanjung Priok’s data was better because it was derived over seven years. He also said both ports have a similar mix of port and non-port areas that make them bright.

Explore an interactive map showcasing onshore and offshore light radiance separately, utilizing NIO’s data. Hover your mouse cursor to examine light radiance along Karachi’s coast. In the modified roadmap view, discover the names of various areas across the city’s coastline. Created by Ammaz Khan.

How artificial light disrupts

In 2022, a study on the impact of ALAN in marine ecosystems was published by Dr Thomas Davies, marine conservation expert at the University of Plymouth. The study showed:

- It can disrupt reproduction of coral species and fishes in the Indo-Pacific Ocean, reducing their populations over time.

- Light intensity may have an effect on microphytobenthos or tiny algae.

- It may alter macroalgae or larger algae that produce food in the sea.

- ALAN poses risks to baby turtles trying to reach the sea after hatching.

- It can disorientate young seabirds, affecting their ability to fly properly.

Pakistani experts confirmed ALAN’s impact on marine ecology. According to Dr Sadia Khalil at Karachi’s Pakistan Marine and Environment Lab, it can disrupt the behaviour of zooplanktons, tiny sea creatures that rise up to the surface at night to feast on microalgae, a process known as Diel Vertical Migration. The zooplanktons carry carbon from the surface to depth of the sea around 200 metres. This carbon then sinks to the bottom of the ocean and sequestrates (long-term storage of carbon in the sea) for a long period. This maintains cooler sea temperatures and regulates the surface carbon levels in the atmosphere.

But ALAN halts this process making the sea warmer. Dr Khalil cited a 2013 study conducted in the Arctic’s super dark winter, a period of time when the Arctic region is in complete or near complete darkness for several months. It showed Calanus copepods, a kind of zooplankton, when exposed to white, blue, green, and red lights, were super sensitive to blue and green artificial lights that penetrate deeper into the water column than red light. The following two animation explains:

The first animation illustrates the occurrence of diel vertical migration in natural light, while the second animation depicts this migration under severe ALAN influence. Animations by Muhammad Yousuf.

Dr Shoaib Kiyani from Karachi University’s marine sciences department further added that copepods are the main zooplanktons found plentiful in Karachi’s sea. ALAN can unsettle the ocean’s food chain. When copepods stay below the surface it leaves their predators hungry. Herring, sardines and mullets are the first-level consumers of copepods. They are the link between zooplankton and bigger fishes,

Dr Kiyani said that the predators of these fishes include dolphins, whales, sharks and seabirds. Sardines are food for bigger fish or turned into chicken feed but their population is decreasing in the Arabian Sea. Illegal fishing methods and rising water temperatures are seen as major causes, But ALAN’s impact on sardine population hadn’t been studied yet, said Dr Kiyani. The drop in their numbers affects the entire seafood ecosystem.

Sindh Trawler Owners Association president Habibullah Niazi agreed with Dr Kiyani about the drop in sardine population. He said that around 35 years ago, large schools of sardine fishes were common in the region, but now they hardly appeared. When I told him about ALAN and its influence on maritime fauna, he countered saying that there were unlit coasts in the region and questioned how light pollution could impact marine life. Illegal fishing practices and other kinds of marine pollution had caused declines in fish population, he argued.

A fisherman, Muhammad Sadiq from Rehri Goth, a small picturesque fishing village at Ibrahim Hyderi hills, near the Port Qasim Authority, gave me a first-hand account about the decline in sardines. We spoke on Saturday November 25. He told me that the last time he caught a swarm of sardines, or chaku as he called them, was a few months ago. “Back in the 1990s we would get chaku right here at the Rehri Goth creek. Now they don’t show up for miles.” Back then, they would sell it for PKR30 per kg (USD 0.01, current dollar rate) and now sell it in the market for PKR90 per kg (USD 0.3). He had also noticed that large fishes like grunter or dhotar and black barracuda or kala kund, that prey on sardines, were absent in the sea. The last time Sadiq caught a kala kund was ten years ago.

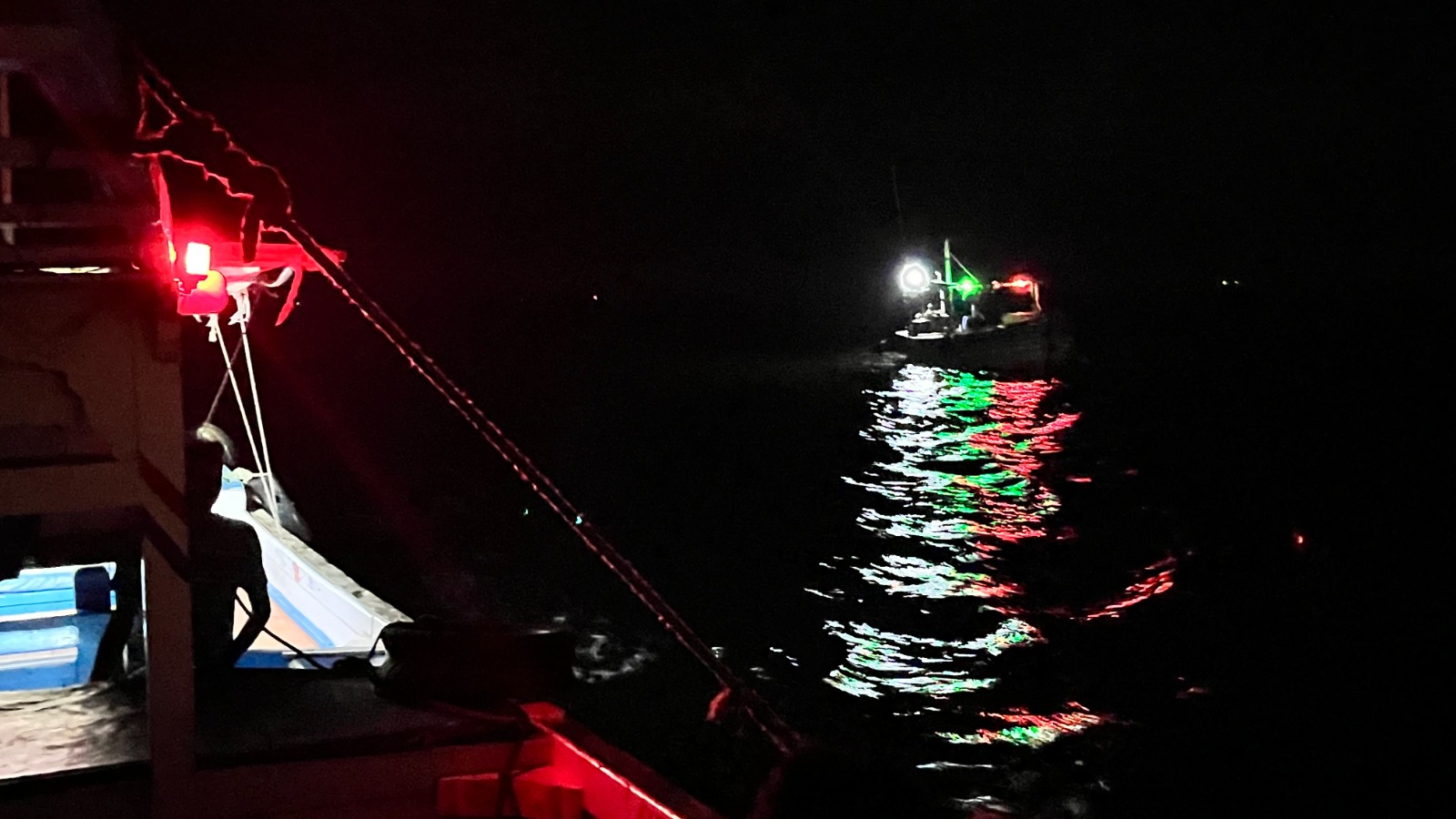

During my visit to the Karachi Port Trust (KPT) on Saturday October 21, I observed a spectacle of lights. High-Pressure Sodium (HPS) lights were mounted on towers in different spots. I noticed numerous fishing boats, small and large, each adorned with about a dozen white LED lights powered by UPS batteries, along with directional green and red lights, that covered the sea.

Numerous HPS mounted on multiple light towers at KPT: Pictures by Pyar Ali

Some had cast 60-to-70-foot-long fishnets in the water, with green or blue lights at their edges, buoying up the surface. Ali Zafar, the captain of our boat, explained that these lights functioned as signals for other boats to avoid getting entangled in the nets, which could damage their engines. He added that a 40-foot-long fishing boat typically carries at least nine 100-watt white LED bulbs to lure fish.

Ships and boats docked at KPT emitting various coloured lights. Picture by Pyar Ali

A fishing boat just outside the KPT channel emits a white light for fishing purpose, alongside its directional lights. Picture by Pyar Ali

I had the chance to speak to Muhammad Jumman, a seasoned fisherman from Rehri Goth, who explained their fishing process. They cast a net into the sea, turn off all the boat’s lights and wait patiently for a school of fish. Once spotted, a fisherman turns on a battery-operated, high-powered searchlight, emitting a bright white light, aimed at the sea. “This way, the fish are drawn towards the net. The duration of this operation depends on how quickly we can gather the fish,” he said.

Jumman recalled that in the 1980s, they did not use artificial lights for fishing. Instead, they would torch a cloth attached to a wooden plank, position it at one end of the boat and use the firelight to attract the fish visible on the sea’s surface towards the net. “Back then, spotting fish on the sea’s surface was a regular occurrence,” he reminisced.

Rehri Goth fishermen explaining the plight of fishing economy in the recent times. Picture by Hunain Ameen

I got in touch again with environment auditor Ghani. He explained that HPS lights, common in the 19th century, were still in use in parts of Karachi. Utilising Dr Davies study, he said that HPS lights, also known as mercury lamps, emit a narrow range of colours, primarily in a yellow-orange spectrum, with a wavelength of around 590 nanometers.

He pointed out that in contrast to HPS lights, LED lights have a broader range of wavelengths depending on the materials used. However, it is their blue glow, which penetrates deeper into the ocean that has a more significant impact on marine ecology.

Natural lights end, guidelines ignored

“When I spend nights at my friend’s place in Defence Housing Authority [an army-administered upscale residential society], the noise of honking cars and traffic disturbs me. I find listening to the waves lapping on the shore in my village helps me fall asleep,” says Zahir.

Advertisements for various housing societies have been installed along the five-km Mubarak Village Road. Karachi mayor initiated in October 2023 the transformation of the road to a dual carriageway to be stippled with LED lights. Earlier in August, the federal government approved an electricity project for the village. These suggest that for the Mubarak Village community, the days of natural lights and pitch black nights are coming to an end.

Moreover, the following high-rise projects do not mention any issues or guidelines relating to artificial light pollution in their documents.

- Within Emaar Pakistan, around 24 buildings are under construction.

- Adjacent to Emaar, a commercial-housing HMR Waterfront project is shaping up on 13 plus hectares of reclaimed land.

- The Sindh government is building a Peoples’ Marine Walk Project, without an EIA, on a 32-acre site, eight kms east of the KPT. This project includes plans to install LED lights on its pathways, 36 shops, 12 cafes and 70 kiosks, according to documents obtained by The Citizenry.

I contacted Naeem Mughal, Director General Sindh Environment Protection Agency, provincial environmental body. He said that light pollution “was not much of a big issue in Karachi. Only a small portion of the city’s shoreline was developed [urbanised], where we have higher light intensity”. He also said that if a study highlighted the risks of light pollution, his agency could issue guidelines during the planning and development stages.

Radiance of high rises near Karachi’s shores

Dr Ahmed of Hasselt University conducted an independent

study to understand the brightness near Karachi’s shore. He measured light radiance emitted

from tall buildings in January and February 2023. Unlike the NIO, he did not create ranges

and buffers, but provided average radiance values of the two months, separately. Following

were his findings.’

- The 62-storey Bahria Icon Tower, Pakistan’s tallest building located near the Clifton beach, 1.6 kms from the sea, emitted light with 88 W and 63.96 W intensities in January and February respectively.

- The 35-storey Sky Tower, 420 metres away from the shore, gave off around 19.6 W during both January and February.

- The Dolmen Mall Clifton (DMC), 434 ms from the sea, emitted radiance of 87.4 W and 37.7 W in January and February separately.

- The Nueplex Cinema, 3.8 kms from the sea and 620 ms from the Gizri Creek, had a radiance of 40.6 W and 33.8 W in January and February respectively.

Ahmed noted that since these averages represent two months, even if a building didn’t emit light for just one night, it would lower the overall monthly average. Hence, the substantial difference in light radiance, from the DMC, between January and February suggests a likely power outage in February for one night, significantly reducing the month’s mean value. Ahmed also found the influence of onshore ALAN intricately tied to built-up density. He explained that the presence of concrete surfaces contributed to the albedo effect (the ability of a surface to reflect sunlight), resulting in a heightened reflection of light towards nearby shores.

Light emissions from Karachi’s mangroves

Dr Ahmed of Hasselt University measured the average radiance levels in different mangrove areas of Karachi during January and February 2023. Following were his findings.

- Near KPT mangroves it ranged between 4.2 W and 5 W

- Around Sandspit mangroves it was 1.9 W and 2.1 W

- In the Gizri Creek mangroves it was 6.7 W and 7.6 W

- Near Ibrahim Hyderi, a small fishing village, in the Korangi Creek mangroves, the ALAN ranges between 2.5 W and 2.7 W.

- In the Karachi Export Processing Zone at PQA, it was 1.9 W in both months.

He explained that offshore ALAN exhibited variations, with higher radiance observed near ports and decreased luminosity in mangrove areas. “This discrepancy may be attributed partly to the limited density of installed lights in these regions.” Shabib Asghar in his article wrote that in the aftermath of cyclone Biparjoy, mangroves (in Karachi) were seen protecting land from the storm’s destructive effects. Mangroves not only safeguard coastal communities from tsunamis and cyclones but are also a nursery for fish and other marine life. Additionally, as per the ALAN data provided by Ahmed, these mangroves seemed to act as buffers against the artificial light at night for marine species.

Interactive maps displaying the light radiance of Karachi’s highrises and mangroves separately, based on data provided by Dr. Ahmed. The first map represents January, and the second represents February. Created by Zubair Ahmed.

Smart lighting: solutions for coastal safety and marine life

- She also recommended eliminating unnecessary lights, using timers and dimmers and choosing marine-friendly lights like amber, orange or red LEDs.

- She said other ways to reduce light pollution are lowering the height and wattage of the lights and planting thick dune vegetation to control light from reaching the beach when the light source is hardly 50 feet away.

- She urged the government to come up with a lighting ordinance for the beaches, especially where marine turtles nest.

Header video by Pyar Ali

Subedited by Maleeha Hamid Siddiqui

Story produced with support from Internews’ Earth Journalism Network.

CREDITS

Senior Editor

Amrita Gupta, Earth Journalism Network

Senior Editor

Maleeha Hamid Siddiqui

Senior subeditor

Bilal Ahmed, The News International

Karachi Desk

Web Developer

Muhammad Yousuf

This story owes its existence to the unwavering support of the following

individuals:

Muhammad Usman Ghani

Dr Sadia Khalil

Pyar Ali

Ammaz Khan

Buraq Shabbir

Sibte Hassan

Hunain Ameen

Ahmad Shabbar

Faysal Rehman

Zubair

Ahmad